Quick Peek at Active Implementation Framework the Art and Science of Implementiation

- Argue

- Open up Access

- Published:

Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks

Implementation Scientific discipline volume ten, Article number:53 (2015) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

Implementation science has progressed towards increased use of theoretical approaches to provide improve agreement and caption of how and why implementation succeeds or fails. The aim of this article is to suggest a taxonomy that distinguishes between dissimilar categories of theories, models and frameworks in implementation science, to facilitate appropriate selection and application of relevant approaches in implementation research and exercise and to foster cross-disciplinary dialogue amongst implementation researchers.

Discussion

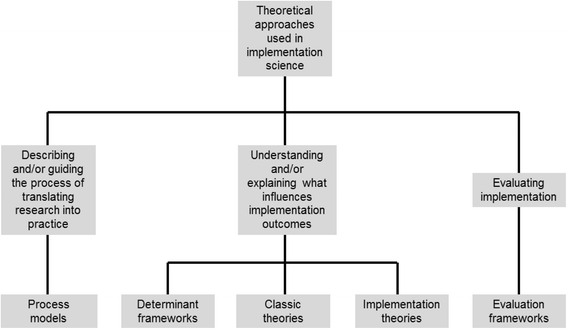

Theoretical approaches used in implementation science take 3 overarching aims: describing and/or guiding the process of translating research into exercise (process models); understanding and/or explaining what influences implementation outcomes (determinant frameworks, classic theories, implementation theories); and evaluating implementation (evaluation frameworks).

Summary

This article proposes five categories of theoretical approaches to achieve three overarching aims. These categories are not always recognized every bit split types of approaches in the literature. While there is overlap between some of the theories, models and frameworks, sensation of the differences is important to facilitate the option of relevant approaches. Most determinant frameworks provide express "how-to" support for carrying out implementation endeavours since the determinants normally are too generic to provide sufficient detail for guiding an implementation process. And while the relevance of addressing barriers and enablers to translating enquiry into do is mentioned in many process models, these models do non identify or systematically structure specific determinants associated with implementation success. Furthermore, procedure models recognize a temporal sequence of implementation endeavours, whereas determinant frameworks do not explicitly take a process perspective of implementation.

Groundwork

Implementation science was borne out of a want to address challenges associated with the utilize of research to achieve more show-based practise (EBP) in health intendance and other areas of professional practice. Early implementation research was empirically driven and did non ever pay attention to the theoretical underpinnings of implementation. Eccles et al. ([1]:108) remarked that this inquiry seemed like "an expensive version of trial-and-error". A review of guideline implementation strategies by Davies et al. [2] noted that only 10% of the studies identified provided an explicit rationale for their strategies. Mixed results of implementing EBP in various settings were often attributed to a express theoretical footing [ane,3-v]. Poor theoretical underpinning makes it difficult to understand and explicate how and why implementation succeeds or fails, thus restraining opportunities to identify factors that predict the likelihood of implementation success and develop ameliorate strategies to achieve more successful implementation.

Even so, the final decade of implementation science has seen wider recognition of the need to institute the theoretical bases of implementation and strategies to facilitate implementation. There is mounting interest in the utilize of theories, models and frameworks to gain insights into the mechanisms past which implementation is more likely to succeed. Implementation studies now utilise theories borrowed from disciplines such every bit psychology, sociology and organizational theory equally well as theories, models and frameworks that accept emerged from within implementation science. In that location are now so many theoretical approaches that some researchers have complained most the difficulties of choosing the most appropriate [6-11].

This commodity seeks to further implementation science by providing a narrative review of the theories, models and frameworks applied in this research field. The aim is to describe and analyse how theories, models and frameworks take been applied in implementation science and propose a taxonomy that distinguishes betwixt different approaches to advance clarity and attain a common terminology. The appetite is to facilitate advisable option and application of relevant approaches in implementation studies and foster cross-disciplinary dialogue among implementation researchers. The importance of a clarifying taxonomy has evolved during the many discussions on theoretical approaches used inside implementation science that the author has had over the past few years with fellow implementation researchers, too as reflection on the utility of dissimilar approaches in various situations.

Implementation science is divers as the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other EBPs into routine do to amend the quality and effectiveness of wellness services and care [12]. The terms knowledge translation, knowledge exchange, knowledge transfer, cognition integration and research utilization are used to describe overlapping and interrelated research on putting various forms of knowledge, including inquiry, to use [8,13-16]. Implementation is part of a diffusion-dissemination-implementation continuum: improvidence is the passive, untargeted and unplanned spread of new practices; dissemination is the active spread of new practices to the target audition using planned strategies; and implementation is the process of putting to use or integrating new practices within a setting [sixteen,17].

A narrative review of selective literature was undertaken to identify key theories, models and frameworks used in implementation science. The narrative review approach gathers information about a detail subject from many sources and is considered appropriate for summarizing and synthesizing the literature to draw conclusions near "what we know" about the subject field. Narrative reviews yield qualitative results, with strengths in capturing diversities and pluralities of understanding [xviii,19]. Six textbooks that provide comprehensive overviews of research regarding implementation science and implementation of EBP were consulted: Rycroft-Malone and Bucknall [20], Nutley et al. [21], Greenhalgh et al. [17], Grol et al. [22], Straus et al. [23] and Brownson et al. [24]. A few papers presenting overviews of theories, models and frameworks used in implementation science were besides used: Estabrooks et al. [fourteen], Sales et al. [4], Graham and Tetroe [25], Mitchell et al. [8], Flottorp et al. [26], Meyers et al. [27] and Tabak et al. [28]. In add-on, Implementation Science (beginning published in 2006) was searched using the terms "theory", "model" and "framework" to identify relevant articles. The titles and abstracts of the identified articles were scanned, and those that were relevant to the study aim were read in full.

Discussion

Theories, models and frameworks in the general literature

Generally, a theory may be divers as a set of belittling principles or statements designed to structure our observation, agreement and explanation of the earth [29-31]. Authors unremarkably point to a theory as being fabricated up of definitions of variables, a domain where the theory applies, a set of relationships between the variables and specific predictions [32-35]. A "skillful theory" provides a clear explanation of how and why specific relationships lead to specific events. Theories can be described on an brainchild continuum. High abstraction level theories (general or thou theories) have an almost unlimited scope, eye abstraction level theories explain limited sets of phenomena and lower level abstraction theories are empirical generalizations of express scope and application [30,36].

A model typically involves a deliberate simplification of a miracle or a specific aspect of a phenomenon. Models demand not be completely accurate representations of reality to take value [31,37]. Models are closely related to theory and the divergence between a theory and a model is not always clear. Models tin can be described equally theories with a more narrowly divers scope of caption; a model is descriptive, whereas a theory is explanatory as well equally descriptive [29].

A framework usually denotes a construction, overview, outline, arrangement or plan consisting of various descriptive categories, due east.chiliad. concepts, constructs or variables, and the relations between them that are presumed to account for a phenomenon [38]. Frameworks exercise not provide explanations; they simply depict empirical phenomena by fitting them into a set of categories [29].

Theories, models and frameworks in implementation science

Information technology was possible to identify three overarching aims of the employ of theories, models and frameworks in implementation science: (i) describing and/or guiding the process of translating research into practise, (two) understanding and/or explaining what influences implementation outcomes and (3) evaluating implementation. Theoretical approaches which aim at understanding and/or explaining influences on implementation outcomes (i.e. the 2nd aim) can be farther broken downwards into determinant frameworks, classic theories and implementation theories based on descriptions of their origins, how they were developed, what knowledge sources they drew on, stated aims and applications in implementation science. Thus, five categories of theoretical approaches used in implementation science can be delineated (Table 1; Figure 1):

Three aims of the use of theoretical approaches in implementation science and the five categories of theories, models and frameworks.

-

Process models

-

Determinant frameworks

-

Classic theories

-

Implementation theories

-

Evaluation frameworks

Although theories, models and frameworks are singled-out concepts, the terms are sometimes used interchangeably in implementation science [nine,14,39]. A theory in this field unremarkably implies some predictive chapters (e.g. to what extent practise health care practitioners' attitudes and behavior concerning a clinical guideline predict their adherence to this guideline in clinical practice?) and attempts to explicate the causal mechanisms of implementation. Models in implementation scientific discipline are commonly used to describe and/or guide the process of translating research into practise (i.e. "implementation do") rather than to predict or analyse what factors influence implementation outcomes (i.eastward. "implementation research"). Frameworks in implementation science frequently have a descriptive purpose by pointing to factors believed or plant to influence implementation outcomes (east.m. health intendance practitioners' adoption of an evidence-based patient intervention). Neither models nor frameworks specify the mechanisms of change; they are typically more similar checklists of factors relevant to various aspects of implementation.

Describing and/or guiding the process of translating research into practise

Process models

Process models are used to describe and/or guide the process of translating research into practice. Models by Huberman [40], Landry et al. [41], the CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Wellness Research) Noesis Model of Knowledge Translation [42], Davis et al. [43], Majdzadeh et al. [44] and the K2A (Cognition-to-Activeness) Framework [15] outline phases or stages of the inquiry-to-practice process, from discovery and product of research-based knowledge to implementation and use of research in diverse settings.

Early on research-to-exercise (or knowledge-to-action) models tended to depict rational, linear processes in which research was but transferred from producers to users. However, subsequent models have highlighted the importance of facilitation to support the process and placed more emphasis on the contexts in which research is implemented and used. Thus, the attention has shifted from a focus on production, improvidence and dissemination of enquiry to diverse implementation aspects [21].

So-called activity (or planned action) models are process models that facilitate implementation by offering practical guidance in the planning and execution of implementation endeavours and/or implementation strategies. Action models elucidate important aspects that demand to be considered in implementation practise and usually prescribe a number of stages or steps that should be followed in the process of translating research into practice. Activeness models have been described equally agile by Graham et al. ([45]:185) considering they are used "to guide or cause change". Information technology should be noted that the terminology is not fully consistent, as some of these models are referred to as frameworks, for example the Knowledge-to-Action Framework [46].

Many of the action models originate from the nursing-led field of enquiry use/utilization; well-known examples include the Stetler Model [47], the ACE (Academic Center for Evidence-Based Practice) Star Model of Knowledge Transformation [48], the Knowledge-to-Action Framework [thirteen], the Iowa Model [49,fifty] and the Ottawa Model [51,52]. There are also numerous examples of similar "how-to-implement" models that have emerged from other fields, including models developed past Grol and Wensing [53], Pronovost et al. [54] and the Quality Implementation Framework [27], all of which are intended to provide support for planning and managing implementation endeavours.

The how-to-implement models typically emphasize the importance of careful, deliberate planning, especially in the early on stages of implementation endeavours. In many ways, they nowadays an ideal view of implementation exercise as a process that gain step-wise, in an orderly, linear way. Still, authors behind well-nigh models emphasize that the actual process is not necessarily sequential. Many of the action models mentioned here have been subjected to testing or evaluation, and some take been widely applied in empirical enquiry, underscoring their usefulness [9,55].

The process models vary with regard to how they were developed. Models such as the Stetler Model [47,56] and the Iowa Model [49,50] were based on the originators' ain experiences of implementing new practices in various settings (although they were besides informed by enquiry and expert opinion). In contrast, models such as the Knowledge-to-Action Framework [45] and the Quality Implementation Framework [27] accept relied on literature reviews of theories, models, frameworks and individual studies to identify key features of successful implementation endeavours.

Understanding and explaining what influences implementation outcomes

Determinant frameworks

Determinant frameworks describe general types (also referred to as classes or domains) of determinants that are hypothesized or have been found to influence implementation outcomes, e.k. health intendance professionals' behaviour change or adherence to a clinical guideline. Each type of determinant typically comprises a number of individual barriers (hinders, impediments) and/or enablers (facilitators), which are seen as contained variables that take an impact on implementation outcomes, i.e. the dependent variable. Some frameworks too hypothesize relationships between these determinants (east.g. [17,57,58]), whereas others recognize such relationships without clarifying them (due east.g. [59,60]). Data about what influences implementation outcomes is potentially useful for designing and executing implementation strategies that aim to alter relevant determinants.

The determinant frameworks exercise not address how change takes place or any causal mechanisms, underscoring that they should not exist considered theories. Many frameworks are multilevel, identifying determinants at different levels, from the private user or adopter (east.g. health care practitioners) to the organisation and beyond. Hence, these integrative frameworks recognize that implementation is a multidimensional phenomenon, with multiple interacting influences.

The determinant frameworks were developed in unlike ways. Many frameworks (e.g. [17,21,22,57,59,61]) were developed by synthesizing results from empirical studies of barriers and enablers for implementation success. Other frameworks have relied on existing determinant frameworks and relevant theories in various disciplines, due east.g. the frameworks by Gurses et al. [58] and CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) [lx].

Several frameworks have drawn extensively on the originator'due south own experiences of implementing new practices. For instance, the Understanding-User-Context Framework [62] and Active Implementation Frameworks [63] were both based on a combination of literature reviews and the originators' implementation experiences. Meanwhile, PARIHS (Promoting Activeness on Research Implementation in Health Services) [v,64] emerged from the observation that successful implementation in health care might be premised on three key determinants (characteristics of the evidence, context and facilitation), a proposition which was then analysed in four empirical instance studies; PARIHS has later on undergone substantial inquiry and development work [64] and has been widely applied [65].

Theoretical Domains Framework represents another approach to developing determinant frameworks. It was synthetic on the basis of a synthesis of 128 constructs related to behaviour modify found in 33 behaviour change theories, including many social cognitive theories [10]. The constructs are sorted into 14 theoretical domains (originally 12 domains), e.yard. cognition, skills, intentions, goals, social influences and behavior about capabilities [66]. Theoretical Domains Framework does not specify the causal mechanisms found in the original theories, thus sharing many characteristics with determinant frameworks.

The determinant frameworks account for five types of determinants, as shown in Table 2, which provides details of eight of the virtually commonly cited frameworks in implementation science. The frameworks are superficially quite disparate, with a broad range of terms, concepts and constructs too equally different outcomes, yet they are quite like with regard to the general types of determinants they account for. Hence, implementation researchers agree to a large extent on what the main influences on implementation outcomes are, albeit to a lesser extent on which terms that are all-time used to depict these determinants.

The frameworks draw "implementation objects" in terms of enquiry, guidelines, interventions, innovations and evidence (i.eastward. research-based knowledge in a broad sense). Outcomes differ correspondingly, from adherence to guidelines and research utilize, to successful implementation of interventions, innovations, evidence, etc. (i.e. the awarding of research-based knowledge in exercise). The relevance of the terminate users (e.one thousand. patients, consumers or customs populations) of the implemented object (e.g. an EBP) is non explicitly addressed in some frameworks (e.1000. [17,21,67]), suggesting that this is an area where farther research is needed for better analysis of how various end users may influence implementation effectiveness.

Determinant frameworks imply a systems approach to implementation because they indicate to multiple levels of influence and admit that there are relationships within and across the levels and different types of determinants. A system can be understood but as an integrated whole because information technology is composed not only of the sum of its components but as well by the relationships among those components [68]. However, determinants are often assessed individually in implementation studies (e.m. [69-72]), (implicitly) bold a linear relationship between the determinants and the outcomes and ignoring that individual barriers and enablers may interact in various ways that can be hard to predict. For instance, there could exist synergistic effects such that 2 seemingly minor barriers constitute an important obstruction to successful outcomes if they interact. Another issue is whether all relevant barriers and enablers are examined in these studies, which are often based on survey questionnaires, and are thus biased by the researcher's selection of determinants. Surveying the perceived importance of a finite ready of predetermined barriers tin yield insights into the relative importance of these detail barriers merely may overlook factors that independently affect implementation outcomes. Furthermore, in that location is the issue of whether the barriers and enablers are the actual determinants (i.eastward. whether they have really been experienced or encountered) and the extent to which they are perceived to exist (i.e. they are more than hypothetical barriers and enablers). The perceived importance of detail factors may not ever correspond with the actual importance.

The context is an integral role of all the determinant frameworks. Described as "an important but poorly understood mediator of modify and innovation in health care organizations" ([73]:79), the context lacks a unifying definition in implementation science (and related fields such as organizational behaviour and quality improvement). Still, context is generally understood as the weather or surroundings in which something exists or occurs, typically referring to an analytical unit that is college than the phenomena directly under investigation. The role afforded the context varies, from studies (e.thousand. [74-77]) that essentially view the context in terms of a concrete "environment or setting in which the proposed modify is to exist implemented" ([5]:150) to studies (e.m. [21,74,78]) that assume that the context is something more active and dynamic that greatly affects the implementation procedure and outcomes. Hence, although implementation science researchers concur that the context is a critically important concept for agreement and explaining implementation, there is a lack of consensus regarding how this concept should be interpreted, in what means the context is manifested and the ways by which contextual influences might be captured in research.

The different types of determinants specified in determinant frameworks can be linked to archetype theories. Thus, psychological theories that delineate factors influencing private behaviour change are relevant for analysing how user/adopter characteristics impact implementation outcomes, whereas organizational theories concerning organizational climate, culture and leadership are more than applicable for addressing the influence of the context on implementation outcomes.

Archetype theories

Implementation researchers are also wont to apply theories from other fields such every bit psychology, sociology and organizational theory. These theories accept been referred to as classic (or classic change) theories to distinguish them from research-to-do models [45]. They might be considered passive in relation to activity models because they describe change mechanisms and explain how modify occurs without ambitions to actually bring about change.

Psychological behaviour change theories such as the Theory of Reasoned Activity [79], the Social Cognitive Theory [80,81], the Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour [82] and the Theory of Planned Behaviour [83] have all been widely used in implementation scientific discipline to study determinants of "clinical behaviour" change [84]. Theories such as the Cerebral Continuum Theory [85], the Novice-Expert Theory [86], the Cognitive-Experiential Cocky-Theory [87] and addiction theories (eastward.g. [88,89]) may also be applicable for analysing cerebral processes involved in clinical decision-making and implementing EBP, but they are non every bit extensively used every bit the behaviour modify theories.

Theories regarding the collective (such as health care teams) or other aggregate levels are relevant in implementation science, due east.g. theories concerning professions and communities of exercise, likewise as theories concerning the relationships betwixt individuals, e.g. social networks and social uppercase [14,53,90-93]. Notwithstanding, their utilise is not as prevalent every bit the individual-level theories.

There is increasing involvement amongst implementation researchers in using theories concerning the organizational level because the context of implementation is condign more widely best-selling as an important influence on implementation outcomes. Theories apropos organizational civilisation, organizational climate, leadership and organizational learning are relevant for understanding and explaining organizational influences on implementation processes [21,53,57,94-101]. Several arrangement-level theories might have relevance for implementation science. For case, Estabrooks et al. [14] have proposed the utilize of the Situated Alter Theory [102] and the Institutional Theory [103,104], whereas Plsek and Greenhalgh [105] take suggested the use of complexity science [106] for improve understanding of organizations. Meanwhile, Grol et al. [22] have highlighted the relevance of economic theories and theories of innovative organizations. However, despite increased interest in organizational theories, their actual apply in empirical implementation studies thus far is relatively limited.

The Theory of Diffusion, as popularized through Rogers' work on the spread of innovations, has likewise influenced implementation science. The theory's notion of innovation attributes, i.e. relative advantage, compatibility, complication, trialability and observability [107], has been widely applied in implementation scientific discipline, both in private studies (east.chiliad. [108-110]) and in determinant frameworks (e.thou. [17,58,threescore]) to appraise the extent to which the characteristics of the implementation object (e.thou. a clinical guideline) impact implementation outcomes. Furthermore, the Theory of Diffusion highlights the importance of intermediary actors (opinion leaders, change agents and gate-keepers) for successful adoption and implementation [107], which is reflected in roles described in numerous implementation determinant frameworks (e.g. [63,64]) and implementation strategy taxonomies (e.g. [111-114]). The Theory of Improvidence is considered the single nearly influential theory in the broader field of knowledge utilization of which implementation scientific discipline is a part [115].

Implementation theories

There are also numerous theories that have been developed or adjusted by researchers for potential use in implementation science to achieve enhanced understanding and explanation of sure aspects of implementation. Some of these take been adult by modifying sure features of existing theories or concepts, eastward.g. concerning organizational climate and culture. Examples include theories such as Implementation Climate [116], Absorptive Capacity [117] and Organizational Readiness [118]. The adaptation allows researchers to prioritize aspects considered to be most critical to analyse issues related to the how and why of implementation, thus improving the relevance and appropriateness to the detail circumstances at hand.

COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour) represents another approach to developing theories that might exist applicative in implementation science. This theory began by identifying motivation as a process that energizes and directs behaviour. Adequacy and opportunity were added every bit necessary weather for a volitional behaviour to occur, given sufficient motivation, on the basis of a United states consensus meeting of behavioural theorists and a principle of US criminal law (which considers prerequisites for performance of specified volitional behaviours) [119]. COM-B posits that capability, opportunity and motivation generate behaviour, which in turn influences the iii components. Opportunity and capability can influence motivation, while enacting a behaviour tin alter capability, motivation and opportunity [66].

Some other theory used in implementation science, the Normalization Procedure Theory [120], began life as a model, synthetic on the basis of empirical studies of the implementation of new technologies [121]. The model was later expanded upon and developed into a theory as change mechanisms and interrelations between various constructs were delineated [122]. The theory identifies four determinants of embedding (i.e. normalizing) complex interventions in practice (coherence or sense making, cerebral participation or engagement, collective action and reflexive monitoring) and the relationships between these determinants [123].

Evaluating implementation

Evaluation frameworks

There is a category of frameworks that provide a structure for evaluating implementation endeavours. Two mutual frameworks that originated in public health are RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) [124] and PRECEDE-PROCEED (Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation-Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development) [125]. Both frameworks specify implementation aspects that should be evaluated equally part of intervention studies.

Proctor et al. [126] have developed a framework of implementation outcomes that tin can be practical to evaluate implementation endeavours. On the footing of a narrative literature review, they propose eight conceptually singled-out outcomes for potential evaluation: acceptability, adoption (as well referred to as uptake), appropriateness, costs, feasibility, allegiance, penetration (integration of a do within a specific setting) and sustainability (also referred to as maintenance or institutionalization).

Although evaluation frameworks may exist considered in a category of their own, theories, models and frameworks from the other four categories tin likewise be applied for evaluation purposes because they specify concepts and constructs that may exist operationalized and measured. For instance, Theoretical Domains Framework (e.yard. [127,128]), and Normalization Process Theory [129] and COM-B (eastward.m. [130,131]) have all been widely used every bit evaluation frameworks. Furthermore, many theories, models and frameworks have spawned instruments that serve evaluation purposes, eastward.g. tools linked to PARIHS [132,133], CFIR [134] and Theoretical Domains Framework [135]. Other examples include the EBP Implementation Scale to measure out the extent to which EBP is implemented [136] and the BARRIERS Scale to identify barriers to research utilise [137], likewise as instruments to operationalize theories such as Implementation Climate [138] and Organizational Readiness [139].

Summary

Implementation scientific discipline has progressed towards increased utilize of theoretical approaches to address various implementation challenges. While this article is not intended as a complete catalogue of all individual approaches available in implementation scientific discipline, it is obvious that the menu of potentially useable theories, models and frameworks is extensive. Researchers in the field have pragmatically looked into other fields and disciplines to find relevant approaches, thus emphasizing the interdisciplinary and multiprofessional nature of the field.

This article proposes a taxonomy of five categories of theories, models and frameworks used in implementation science. These categories are not always recognized as split up types of approaches in the literature. For example, systematic reviews and overviews by Graham and Tetroe [25], Mitchell et al. [8], Flottorp et al. [26], Meyers et al. [27] and Tabak et al. [28] have non distinguished betwixt process models, determinant frameworks or classic theories because they all deal with factors believed or found to have an touch on on implementation processes and outcomes. Notwithstanding, what matters well-nigh is not how an individual arroyo is labelled; information technology is important to recognize that these theories, models and frameworks differ in terms of their assumptions, aims and other characteristics, which have implications for their use.

There is considerable overlap between some of the categories. Thus, determinant frameworks, classic theories and implementation theories can too help to guide implementation practice (i.e. functioning equally action models), because they identify potential barriers and enablers that might exist important to address when undertaking an implementation endeavour. They tin also exist used for evaluation considering they describe aspects that might exist important to evaluate. A framework such as the Active Implementation Frameworks [68] appears to have a dual aim of providing hands-on support to implement something and identifying determinants of this implementation that should exist analysed. Somewhat similarly, PARIHS [five] tin be used by "anyone either attempting to become testify into practice, or anyone who is researching or trying to improve empathize implementation processes and influences" ([64]:120), suggesting that it has ambitions that go beyond its master function equally a determinant framework.

Despite the overlap betwixt different theories, models and frameworks used in implementation science, knowledge virtually the three overarching aims and five categories of theoretical approaches is important to identify and select relevant approaches in various situations. Almost determinant frameworks provide express "how-to" back up for conveying out implementation endeavours since the determinants may be as well generic to provide sufficient detail for guiding users through an implementation process. While the relevance of addressing barriers and enablers to translating enquiry into practice is mentioned in many process models, these models do non identify or systematically structure specific determinants associated with implementation success. Another fundamental deviation is that procedure models recognize a temporal sequence of implementation endeavours, whereas determinant frameworks do not explicitly accept a process perspective of implementation since the determinants typically relate to implementation as a whole.

Theories applied in implementation science tin can be characterized as middle level. College level theories tin can be built from theories at lower abstraction levels, and so-called theory ladder climbing [140]. May [141] has discussed how a "general theory of implementation" might exist constructed past linking the four constructs of Normalization Procedure Theory with constructs from relevant sociology and psychology theories to provide a more comprehensive explanation of the constituents of implementation processes. Still, it seems unlikely that there will e'er exist a grand implementation theory since implementation is too multifaceted and complex a phenomenon to let for universal explanations. At that place has been contend in the policy implementation research field for many years whether researchers should strive to produce a theory applicable to public policy as a whole [38]. However, policy implementation researchers have increasingly argued that information technology would be a futile undertaking considering "the globe is besides complex and there are too many causes of outcomes to allow for parsimonious explanation" ([37]:31). Determinant frameworks in implementation science conspicuously advise that many different theories are relevant for understanding and explaining the many influences on implementation.

The use of a single theory that focuses only on a particular aspect of implementation will not tell the whole story. Choosing one approach often ways placing weight on some aspects (due east.g. sure causal factors) at the expense of others, thus offering only partial agreement. Combining the claim of multiple theoretical approaches may offer more complete agreement and explanation, yet such combinations may mask contrasting assumptions regarding key issues. For example, are people driven primarily by their individual beliefs and motivation or does a pervasive organizational culture impose norms and values that regulate how people behave and make individual characteristics relatively unimportant? Is a particular behaviour primarily influenced past cogitating idea processes or is it an automatically enacted addiction? Furthermore, dissimilar approaches may require dissimilar methods, based on different epistemological and ontological assumptions.

In that location is a current wave of optimism in implementation science that using theoretical approaches volition contribute to reducing the research-practise gap [4,10,11,63,142]. Although the use of theories, models and frameworks has many advocates in implementation science, there accept as well been critics [143,144], who have argued that theory is not necessarily better than common sense for guiding implementation. Common sense has been divers as a grouping's shared tacit noesis concerning a phenomenon [145]. One could argue that common sense about how or why something works (or does not) besides constitutes a theory, albeit an informal and non-codified ane. In either case, empirical research is needed to study how and the extent to which the apply of implementation theories, models and frameworks contributes to more effective implementation and nether what contextual conditions or circumstances they apply (and do not apply). It is also important to explore how the current theoretical approaches can be further developed to better address implementation challenges. Hence, both anterior construction of theory and deductive application of theory are needed.

While the use of theory does not necessarily yield more than effective implementation than using common sense, there are certain advantages to applying formal theory over mutual sense (i.due east. informal theory). Theories are explicit and open to question and examination; mutual sense ordinarily consists of implicit assumptions, behavior and ways of thinking and is therefore more difficult to challenge. If deductions from a theory are incorrect, the theory tin be adapted, extended or abandoned. Theories are more than consistent with existing facts than common sense, which typically ways that a hypothesis based on an established theory is a more than educated guess than one based on common sense. Furthermore, theories give individual facts a meaningful context and contribute towards edifice an integrated body of knowledge, whereas common sense is more likely to produce isolated facts [145,146]. On the other mitt, theory may serve equally blinders, every bit suggested by Kuhn [147] and Greenwald et al. [148], causing the states to ignore problems that practice not fit into existing theories, models and frameworks or hindering us from seeing known issues in new means. Theorizing about implementation should therefore not be an abstract bookish do unconnected with the real world of implementation practice. In the words of Immanuel Kant, "Feel without theory is blind, but theory without feel is mere intellectual play".

References

-

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts Northward. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:107–12.

-

Davies P, Walker A, Grimshaw J. Theories of beliefs change in studies of guideline implementation. Proc Br Psychol Soc. 2003;xi:120.

-

Michie South, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;xiv:26–33.

-

Sales A, Smith J, Curran G, Kochevar L. Models, strategies, and tools: theory in implementing evidence-based findings into health care practise. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S43–9.

-

Kitson AL, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence-based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7:149–58.

-

ICEBeRG. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006;i:4.

-

Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;3:36.

-

Mitchell SA, Fisher CA, Hastings CE, Silverman LB, Wallen GR. A thematic assay of theoretical models for translating science in nursing: mapping the field. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58:287–300.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Theory, Frameworks, and Models: Laying Down the Background. In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Bear witness-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 23–50.

-

Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour modify and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

-

Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation problems in implementation scientific discipline. Implement Sci. 2014;ix:118.

-

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:one.

-

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:xiii–24.

-

Estabrooks CA, Thompson DS, Lovely JE, Hofmeyer A. A guide to knowledge translation theory. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:25–36.

-

Wilson KM, Brady TJ, Lesesne C, on behalf of the NCCDPHP Work Group on Translation. An organizing framework for translation in public health: the noesis to action framework. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;viii:A46.

-

Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Developing the Terminology for Dissemination and Implementation Research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 23–51.

-

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2005.

-

Jones K. Mission migrate in qualitative research, or moving toward a systematic review of qualitative studies, moving back to a more systematic narrative review. Qual Rep. 2004;9:95–112.

-

Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. Br J Nurs. 2008;17:38–43.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Exercise: Linking Testify to Action. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

-

Nutley SM, Walter I, Davies HTO. Using show: how enquiry can inform public services. Bristol: The Policy Printing; 2007.

-

Grol R, Wensing Thou, Eccles M. Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Clinical Practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2005.

-

Straus South, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Cognition Translation in Wellness Care. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

-

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Broadcasting and Implementation Research in Wellness. New York: Oxford University Printing; 2012.

-

Graham ID, Tetroe J. Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;xiv:936–41.

-

Flottorp SA, Oxman Advertisement, Krause J, Musila NR, Wensing M, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practise: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35.

-

Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The Quality Implementation Framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;l:462–80.

-

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for broadcasting and implementation enquiry. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50.

-

Frankfort-Nachmias C, Nachmias D. Research Methods in the Social Sciences. London: Arnold; 1996.

-

Wacker JG. A definition of theory: research guidelines for unlike theory-building research methods in operations management. J Oper Manag. 1998;sixteen:361–85.

-

Carpiano RM, Daley DM. A guide and glossary on postpositivist theory building for population health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;sixty:564–lxx.

-

Bunge Yard. Scientific Research i: The Search for System. New York: Springer; 1967.

-

Reynolds PD. A Primer in Theory Structure. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing; 1971.

-

Dubin R. Theory Building. New York: Free Press; 1978.

-

Chase SD. Mod Marketing Theory: Critical Bug in the Philosophy of Marketing Science. Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern Publishing; 1991.

-

Bluedorn AC, Evered RD. Eye Range Theory and the Strategies of Theory Construction. In: Pinder CC, Moore LF, editors. Middle Range Theory and The Study of Organizations. Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff; 1980. p. xix–32.

-

Cairney P. Understanding Public Policy—Theories and Issues. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012.

-

Sabatier PA. Theories of the Policy Process. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Printing; 2007.

-

Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey M, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of testify into exercise using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and applied challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1.

-

Huberman Yard. Research utilization: the state of the art. Knowl Policy. 1994;7:13–33.

-

Landry R, Amara Northward, Lamari Yard. Climbing the ladder of enquiry utilization: evidence from social scientific discipline. Sci Commun. 2001;22:396–422.

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). About knowledge translation. [http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html]. Retrieved 18 Dec 2014.

-

Davis SM, Peterson JC, Helfrich CD, Cunningham-Sabo 50. Introduction and conceptual model for utilization of prevention research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:1S.

-

Majdzadeh R, Sadighi J, Nejat Due south, Mahani Equally, Ghdlami J. Knowledge translation for research utilization: design of a knowledge translation model at Teheran Academy of Medical Scientific discipline. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:270–seven.

-

Graham ID, Tetroe J, KT Theories Grouping. Planned Action Theories. In: Straus Southward, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Noesis Translation in Health Care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. p. 185–95.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Analysis and Synthesis of Models and Frameworks. In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Do: Linking Prove to Activeness. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 223–45.

-

Stetler CB. Stetler model. In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Testify to Action. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 51–82.

-

Stevens KR. The bear upon of evidence-based practice in nursing and the next big ideas. Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;18(2):4.

-

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman V, Goode C, Rakel B, Barry-Walker J, et al. Infusing inquiry into practice to promote quality intendance. Nurs Res. 1995;43:307–13.

-

Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ, Rakel BA, Budreau Thou, Everett LQ, et al. The Iowa Model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2001;13:497–509.

-

Logan J, Graham I. Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of wellness intendance research use. Sci Commun. 1998;xx:227–46.

-

Logan J, Graham I. The Ottawa Model of Research Employ. In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 83–108.

-

Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving testify-based exercise. Med J Aust. 2004;180:S57–threescore.

-

Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714.

-

Field B, Booth A, Ilott I, Gerrish Grand. Using the Noesis to Action Framework in do: a citation analysis and systematic review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:172.

-

Stetler C. Refinement of the Stetler/Marram Model for awarding of enquiry findings to practice. Nurs Outlook. 1994;42:fifteen–25.

-

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41:327–50.

-

Gurses AP, Marsteller JA, Ozok AA, Xiao Y, Owens S, Pronovost PJ. Using an interdisciplinary arroyo to identify factors that touch clinicians' compliance with show-based guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(8 Suppl):S282–91.

-

Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray Due south, Dupuis M, Tooman T, Hayes Due south. Gaps between knowing and doing: agreement and assessing the barriers to optimal health intendance. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:94–102.

-

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services inquiry findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;four:50.

-

Ferlie E, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the U.s.a.: a framework for modify. Milbank Q. 2001;79:281–315.

-

Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Development of a framework for knowledge translation: understanding user context. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;viii:94–9.

-

Blase KA, Van Dyke M, Fixsen DL, Bailey FW. Implementation Science: Central Concepts, Themes and Evidence for Practitioners in Educational Psychology. In: Kelly B, Perkins DF, editors. Handbook of Implementation Science for Psychology in Pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. thirteen–34.

-

Rycroft-Malone J. Promoting Activity on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS). In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 109–36.

-

Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, Daggett GS, Sahay A, Ritchie M, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the Promoting Activeness on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2010;5:82.

-

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. A guide to using the Behaviour Change Cycle. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

-

Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation Enquiry: A Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Constitute; 2005.

-

Holmes BJ, Finegood DT, Riley BL, Best A. Systems Thinking in Dissemination and Implementation Research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Inquiry in Health. New York: Oxford University Printing; 2012. p. 192–212.

-

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice. Update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526–35.

-

Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume 50, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health. 2011;33:412–21.

-

Verweij LM, Proper KI, Leffelaar ER, Weel ANH, Nauta AP, Hulshof CTJ, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of an occupational wellness guideline aimed at preventing weight gain amongst employees in the Netherlands. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:954–60.

-

Broyles LM, Rodriguez KL, Kraemer KL, Sevick MA, Price PA, Gordon AJ. A qualitative study of predictable barriers and facilitators to the implementation of nurse-delivered alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for hospitalized patients in a Veterans Affairs medical centre. Addiction Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:7.

-

Dopson S, Fitzgerald L. The Active Role of Context. In: Dopson South, Fitzgerald Fifty, editors. Cognition to Action? Show-Based Wellness Care in Context. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press; 2005. p. 79–103.

-

Ashton CM, Khan MM, Johnson ML, Walder A, Stanberry E, Beyth RJ, et al. A quasi-experimental test of an intervention to increment the use of thiazide-based treatment regimens for people with hypertension. Implement Sci. 2007;two:5.

-

Mohr DC, VanDeusen LC, Meterko One thousand. Predicting healthcare employees' participation in an function redesign program: attitudes, norms and behavioral control. Implement Sci. 2008;iii:47.

-

Scott SD, Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni North, Bize R, Rodgers West. Factors influencing the adoption of an innovation: an examination of the uptake of the Canadian Eye Health Kit (HHK). Implement Sci. 2008;3:41.

-

Zardo P, Collie A. Predicting research use in a public health policy environment: results of a logistic regression analysis. Implement Sci. 2014;nine:142.

-

Gabbay J, Le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed "mindlines"? Ethnographic written report of knowledge direction in primary care. Br Med J. 2011;329:i–5.

-

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour. New York: John Wiley; 1975.

-

Bandura A. Cocky-efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behavioural modify. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

-

Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Cognitive Social Theory. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

-

Triandis HC. Values, Attitudes, and Interpersonal Behaviour. In: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Beliefs, Attitude, and values: 1979. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1979. p. 195–259.

-

Ajzen I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior. Milton Keynes: Open University Press; 1988. **FÖRSVINNER.

-

Nilsen P, Roback K, Broström A, Ellström PE. Creatures of habit: accounting for the function of addiction in implementation research on clinical behaviour change. Implement Sci. 2012;seven:53.

-

Hammond KR. Principles of System in Intuitive and Analytical Cognition. Bedrock, CO: Eye for Research on Judgment and Policy, University of Colorado; 1981.

-

Benner P. From Novice to Expert, Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Exercise. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing; 1984.

-

Epstein S. Integration of the cerebral and the psychodynamic unconscious. Am Psychol. 1994;49:709–24.

-

Ouelette JA, Woods W. Addiction and intention in everyday life: the multiple processes past which by behaviour predicts future behaviour. Psychol Balderdash. 1998;124:54–74.

-

Verplanken B, Aarts H. Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: is habit an empty construct or an interesting instance of goal-directed automaticity? Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 1999;ten:101–34.

-

Eccles MP, Hrisos S, Francis JJ, Steen N, Bosch M, Johnston One thousand. Tin can the collective intentions of individual professionals within healthcare teams predict the team's performance: developing methods and theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4:24.

-

Parchman ML, Scoglio CM, Schumm P. Understanding the implementation of testify-based care: a structural network approach. Implement Sci. 2011;6:14.

-

Cunningham FC, Ranmuthugala Thousand, Plumb J, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J. Health professional person networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000187.

-

Mascia D, Cicchetti A. Md social capital and the reported adoption of evidence-based medicine: exploring the function of structural holes. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:798–805.

-

Wallin L, Ewald U, Wikblad Yard, Scott-Findlay South, Arnetz BB. Agreement work contextual factors: a short-cutting to evidence-based practise? Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006;three:153–64.

-

Meijers JMM, Janssen MAP, Cummings GG, Wallin L, Estabrooks CA, Halfens RYG. Assessing the relationship betwixt contextual factors and research utilization in nursing: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:622–35.

-

Wensing One thousand, Wollersheim H, Grol R. Organizational interventions to implement improvements in patient intendance: a structured review of reviews. Implement Sci. 2006;1:2.

-

Gifford W, Davies B, Edwards N, Griffin P, Lybanon 5. Managerial leadership for nurses' employ of research show: an integrative review of the literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2007;4:126–45.

-

Yano EM. The role of organizational research in implementing evidence-based practice: QUERI series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:29.

-

French B, Thomas LH, Baker P, Burton CR, Pennington 50, Roddam H. What can management theories offer evidence-based do? A comparative analysis of measurement tools for organizational context. Implement Sci. 2009;4:28.

-

Parmelli E, Flodgren Thou, Beyer F, Baillie North, Schaafsma ME, Eccles MP. The effectiveness of strategies to modify organisational civilisation to ameliorate healthcare operation: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:33.

-

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;viii:22.

-

Orlikowski West. Improvising organizational transformation over time: a situated change perspective. Inform Syst Res. 1994;7:63–92.

-

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The New Institutionalism and Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1991.

-

Scott WR. Institutions and Organizations. K Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995.

-

Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. The claiming of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323:625–8.

-

Waldrop MM. Complexity: The Emerging Science at The Border of Order and Anarchy. London: Viking; 1992.

-

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Printing; 2003.

-

Aubert BA, Hamel G. Adoption of smart cards in the medical sector: the Canadian experience. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:879–94.

-

Vollink T, Meertens R, Midden CJH. Innovating 'improvidence of innovation' theory: innovation characteristics and the intention of utility companies to adopt free energy conservation interventions. J Environ Psychol. 2002;22:333–44.

-

Foy R, MacLennan G, Grimshaw J, Penney G, Campbell M, Grol R. Attributes of clinical recommendations that influence modify in exercise following audit and feedback. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:717–22.

-

Oxman Ad, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practise. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–31.

-

Grimshaw J, McAuley LM, Bero LA, Grilli R, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, et al. Systematic reviews of effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Wellness Care. 2003;12:298–303.

-

Walter I, Nutley SM, Davies HTO. Developing a taxonomy of interventions used to increment the affect of inquiry. St. Andrews: Academy of St Andrews; 2003. Discussion Paper three, Research Unit for Research Utilisation, University of St. Andrews.

-

Leeman J, Baernholdt Chiliad, Sandelowski M. Developing a theory-based taxonomy of methods for implementing change in practice. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:191–200.

-

Estabrooks CA, Derksen L, Winther C, Lavis JN, Scott SD, Wallin 50, et al. The intellectual structure and substance of the cognition utilization field: a longitudinal author co-citation analysis, 1945 to 2004. Implement Sci. 2008;3:49.

-

Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manage Rev. 1996;21:1055–80.

-

Zahra As, George One thousand. Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization and extension. Acad Manage Rev. 2002;27:185–203.

-

Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for modify. Implement Sci. 2009;4:67.

-

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour alter bicycle: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

-

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding and integrating practices: an outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology. 2009;43:535.

-

May C, Finch T, Mair F, Ballini L, Dowrick C, Eccles One thousand, et al. Agreement the implementation of complex interventions in health care: the normalization procedure model. Implement Sci. 2007;vii:148.

-

Finch TL, Rapley T, Girling Chiliad, Mair FS, Murray Due east, Treweek S, et al. Improving the normalization of circuitous interventions: measure development based on normalization procedure theory (NoMAD): report protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;eight:43.

-

Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, MacFarlane A, Ballini L, Dowrick C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med. 2010;8:63.

-

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public wellness impact of wellness promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

-

Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

-

Proctor E, Silmere H, RaghaVan R, Hovmand P, Aarons K, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and enquiry calendar. Admin Policy Mental Health. 2011;38:65–76.

-

Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, Lin IB, Loy CT, Rees G, et al. Experiences of using Theoretical Domains Framework beyond diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;viii:139–46.

-

Fleming A, Bradley C, Cullinan South, Byrne Due south. Antibiotic prescribing in long-term care facilities: a qualitative, multidisciplinary investigation. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e006442.

-

McEvoy R, Ballini L, Maltoni South, O'Donnell CA, Mair FS, MacFarlane A. A qualitative systematic review of studies using the normalization process theory to research implementation processes. Implement Sci. 2014;9:2.

-

Connell LA, McMahon NE, Redfern J, Watkins CL, Eng JJ. Evolution of a behaviour modify intervention to increase upper limb exercise in stroke rehabilitation. Implement Sci. 2015;x:34.

-

Praveen D, Patel A, Raghu A, Clifford GD, Maulik PK, Abdul AM, et al. Evolution and field evaluation of a mobile clinical conclusion support system for cardiovascular diseases in rural Republic of india. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2014;two:e54.

-

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Birdell JM, Norton PG. Development and assessment of the Alberta Context Tool. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:234.

-

McCormack B, McCarthy G, Wright J, Slater P, Coffey A. Development and testing of the Context Assessment Alphabetize (CAI). Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6:27–35.

-

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-calibration weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2013;8:51.

-

Dyson J, Lawton R, Jackson C, Cheater F. Evolution of a theory-based musical instrument to identify barriers and levers to best manus hygiene practice among healthcare practitioners. Implement Sci. 2013;8:111.

-

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt Due east, Mays MZ. The Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementation Scales: psychometric properties of 2 new instruments. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5:208–16.

-

Nilsson Kajermo K, Boström A-G, Thompson DS, Hutchinson AM, Estabrooks CA, Wallin L. The BARRIERS calibration—the barriers to research utilization scale: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2010;5:32.

-

Jacobs SR, Weiner BJ, Bunger Ac. Context matters: measuring implementation climate among individuals and groups. Implement Sci. 2014;9:46.

-

Gagnon Grand-P, Labarthe J, Légaré F, Ouimet M, Estabrooks CA, Roch G, et al. Measuring organizational readiness for knowledge translation in chronic care. Implement Sci. 2011;half-dozen:72.

-

Osigweh CAB. Concept fallibility in organizational science. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14:579–94.

-

May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:18.

-

Michie S, Abraham C, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, Hardeman W, Jonston M. Strengthening evaluation and implementation by specifying components of behaviour change interventions: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2011;half-dozen:10.

-

Oxman Advertizing, Fretheim A, Flottorp South. The OFF theory of enquiry utilization. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:113–vi.

-

Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Garfinkel South, Zwarenstein Thou. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions: fine in theory, but prove of effectiveness in practice is needed. Implement Sci. 2006;1:5.

-

Fletcher GJO. Psychology and common sense. Am Psychol. 1984;39:203–thirteen.

-

Cacioppo JT. Common sense, intuition and theory in personality and social psychology. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;eight:114–22.

-

Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. second ed. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press; 1970.

-

Greenwald AG, Pratkanis AR, Leippe MR, Baumgardner MH. Under what atmospheric condition does theory obstruct research progress? Psychol Rev. 1986;93:216–29.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Bianca Albers, Susanne Bernhardsson (special thanks), Dean L. Fixsen, Karen Grimmer, Ursula Reichenpfader and Kerstin Roback for constructive comments on drafts of this article. Also, thank you are due to Margit Neher, Justin Presseau and Jeanette Wassar Kirk for their input.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nil/ane.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Sci 10, 53 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Keywords

- Theory

- Model

- Framework

- Evaluation

- Context

witcherpothumlect.blogspot.com

Source: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

0 Response to "Quick Peek at Active Implementation Framework the Art and Science of Implementiation"

Post a Comment